American Chestnut

Miranda Bellamy and I attended the artist-in-residence program at the Vermont Studio Center for the month of December 2019. VSC is located on the unceded ancestral and contemporary lands of the Western Abenaki people. Today the Abenaki remain unrecognized by the US federal government. We stand in solidarity with the Abenaki people in their ongoing efforts for acknowledgement and reconciliation.

In our practice we look to complicate predominant ways of seeing, to decolonize our worldview, to critically reevaluate ways of knowing, and to queer established systems. We set out to learn more about the land on which we would be visitors as artists in residence at VSC. Through our research we came across the story of Castanea dentata, known as the American chestnut tree.

American chestnut trees were once abundant giants in the forests of eastern North America. They were a highly valued and important resource. In these forests, one in four trees was a chestnut, growing to towering heights and producing a bounty of nuts late in the season. The leaves contained more nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and magnesium than other trees that share its habitat, returning nutrients to the soil in the fall. The lumber was naturally rot resistant. The nuts were nutritious and attracted animals that could be hunted. Nuts were even used as currency in some regions. Almost all were devastated by an introduced fungal blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) in the early 1900s. Four billion trees were lost. The blight persists and prevents American chestnuts from maturing. This keystone species is functionally extinct.

Innovations in biotechnology have made advances toward engineering a blight resistant tree. Regulatory bodies are being lobbied to lift current restrictions so it can be planted in forests with the deliberate intention of spreading freely. Biotechnology has never been used to assist a reforestation effort.

We are interested in the stories, visions, and complications that the American chestnut tree introduces and how these things are embedded in the tree, and in our gesture and artwork, for example: the unforeseen impact that bioengineering could have on wild ecosystems, the inherent issues present in technological utopianism as an approach to climate crisis and to repair damage that has been done, the potential that this tree is a trojan horse for more controversial bioengineering projects in the future, the lack of awareness or access to Indigenous stories of the chestnut tree as the old growth trees disappeared alongside the systemic genocide of Indigenous peoples, the tone of xenophobia we came across in many narratives about the American chestnut tree destroyed by an introduced blight from Asia, the reminder that we have already irreversibly altered all ecosystems and ushered in a new era of the Anthropocene, and the hope that reintroducing the species could have a healing impact on the entire ecosystem and sustain wildlife in the eastern forests in a way that has not been possible since the loss of the chestnuts.

We began our work on the American chestnut tree by making a paste-up based on a historical photograph of an original old growth tree. Tiling 11” x 17” half-tone black and white prints, we reconstructed the image of the tree in a life-sized scale on the studio wall.

Shortly afterward we connected with a member of the American Chestnut Foundation who helped us to locate a mature American chestnut tree in Berlin, Vermont. With permission from the foundation, we drove to the site, walked through the woods, and managed to locate this incredibly rare tree. We spent some time with the tree, observing its surroundings and its stature. We gathered fallen leaves. We took clay impressions of its deeply textured bark. We recorded video footage of the tree and biodata from the moss that grew on its trunk. In the studio, we edited these images and sounds into a video portrait.

After visiting the tree, we used one of our own photographs to make a second paste-up, this time in colour, of the living tree. We incorporated some small shelves with handmade books into the image. The books contain the abstracted patterns and colours of the half-tone image used to make the paste-up.

We discovered that historical American chestnut lumber was still a commodity and reclaimed wood could be purchased on ebay. The old growth trees died standing as a result of the blight, as evidenced by the insect holes that cover this ‘wormy chestnut’ lumber.

We explored many responses to the tree in clay; modeling a larger-than life replica of an American chestnut burr, taking impressions of the ‘wormy chestnut’ lumber, and dipping the collected leaves in slip (a watered down clay) and firing them off in VSC’s kiln. The impressions of the bark that were made on our site visit to the tree were finished with a shining white glaze.

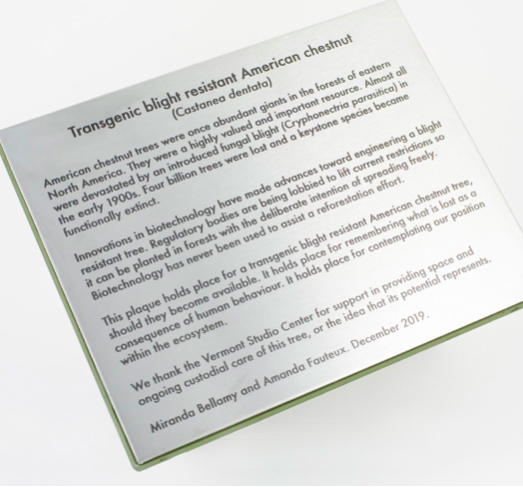

At the end of our residency we unveiled a permanent tree plaque installed on the VSC campus. The plaque holds place for planting a transgenic blight resistant American chestnut tree, should they ever become available. It holds place for remembering what is lost as a consequence of human behaviour. It holds place for contemplating our position within the ecosystem.

We thank the VSC for support in providing space and ongoing custodial care of this tree, or the idea that its potential represents. We also thank the Jan Warburton Charitable Trust for their generous contribution toward Miranda attending the VSC, and the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.